Architecture

is not a modern phenomenon. It began as soon as the early cave man began to

build his own shelter to live in. Man first began to create and fix his own

shelter when he stepped out from the natural habitat of dense jungle covers.

Thus emerged architecture is a combination of needs, imagination, capacities of

the builders and capabilities of the workers.

Architectural

Forms and Construction Details:

Indian

Architecture evolved in various ages in different parts and regions of the

country. Naturally, the emergence and decay of great empires and dynasties

influenced the growth and shaped the evolution of Indian architecture. The art of sculpture began in India during

the Indus Valley civilization which encompassed parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan

and north-west India as far south as Rajkot. Excavations at Indus valley sites

at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in modern-day Pakistan have uncovered a large

quantity of terracotta sculpture and, featuring images of female dancers, animals,

foliage and deities

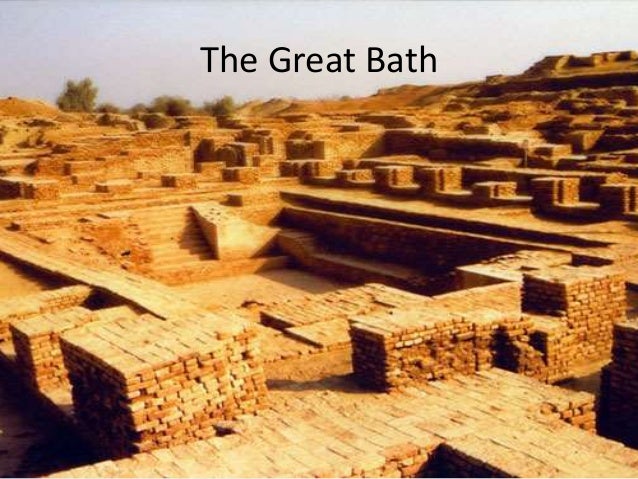

HARAPPAN

PERIOD and Architecture

The excavations at Harappa and Mohenjodaro and

several other sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation revealed the existence of

a very modern urban civilisation with expert town planning and engineering

skills. The very advanced drainage system along with well planned roads and

houses show that a sophisticated and highly evolved culture existed in India

before the coming of the Aryans.

The Harappan people had constructed mainly

three types of buildings-

·

dwelling houses

·

pillared halls and

·

public baths.

Main features of Harappan remains are: 1.

·

All the sites consisted of walled

cities which provided security to the people.

·

The cities had a rectangular grid

pattern of layout with roads that cut each other at right angles.

·

The Indus Valley people used

standardised burnt mud-bricks as building material.

·

There is evidence of building of

big dimensions which were public buildings, administrative or business centres,

pillared halls and courtyards, There is no evidence of temples.

·

Public buildings include granaries

which were used to store grains which give an idea of an organised collection

and distribution system.

·

public bathing place shows the

importance of ritualistic bathing and cleanliness in this culture.

·

It is significant that most of the

houses had private wells and bathrooms.

The

world’s first bronze sculpture of a dancing girl has been found in Mohenjodaro.

The Vedic Aryans who came

next, lived in houses built of wood, bamboo and

reeds; the Aryan culture was largely a rural one. Aryans used perishable

material like wood for the construction of royal palaces which have been

completely destroyed over time.

The most important feature of the Vedic period was the making of fire altars

which soon became an important and integral part of the social and religious

life of the people even today.

Mauryan Sculpture: Pillars of

Ashoka (3rd Century BC)

The story of monumental stone

sculpture begins with the Maurya Dynasty, when sculptors first started to

carve illustrative scenes from India's three main religions - Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.

Jainism, a peace-loving

culture founded by Mahavira during the

6th century BC. Later, a third religious system called Buddhism appeared, based on the teachings of

Gautama Buddha (also known as Siddhartha Gautama, or Buddha), a sage who lived

and taught in eastern India during the 5th century BC.

One of the earliest Mauryan

patrons of the arts was Emperor Ashoka who decided to spread the Buddhist faith

through the construction of 85,000 stupas or dome-shaped monuments, decorated

with Buddhist writings and imagery engraved on rocks and pillars. The finest

example is probably the Great Stupa at Sanchi,

whose carved gateways depict a variety of Buddhist legends. It is believe that

Mauryan sculpture was influenced by Ancient

Persian Art . Other animal images used on the pillars, include bulls and elephants .

Located in a remote valley in the

Aurangabad district of Maharashtra, Western India, the Ajanta Caves are world

famous for their cave

art - paintings and carvings illustrating the life of Buddha. There

are some 29 rock-cut caves in total, five of which were used as temples or

prayer halls, and twenty-four as monasteries.

The parietal

art at Ajanta includes some of the finest masterpieces of Buddhist

iconography in India. In addition to numerous serene statues of Buddha, the

Ajanta sculptures include intricate images of animals, warriors, and deities

while the paintings depict tales of

ancient courtly life and Buddhist legend. The Ajanta Caves were gradually

forgotten until 1819, when they were accidentally rediscovered by a British

officer during a tiger-hunt. Since 1983,

the Ajanta Caves have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Next two distinctive schools of Buddhist visual art emerged during the Kushan Empire in eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan and north-western India,

during the 1st century CE.

The first, known as the Gandhara school (flourished 1st-5th century), was centered around Peshawar. The Gandhara school was noted for its

Greco-Roman style of Buddhist sculpture, partly due to the conquests of

Alexander the Great in the region and the resulting legacy of Hellenistic

art (c.323-30 BCE), as well as the active trade between the territory

and Rome. Borrowing heavily from classical Greek

sculpture as well as Roman

sculpture, Gandharan artists depicted Buddha

with a youthful Apollo-like face, complete with Roman nose, dressed in

toga-style garments like those seen on Roman imperial statues. The most common material used by Gandharan

sculptors was dark grey or green phyllite, grey-blue mica schist, or

terracotta. Their significance lies in the fact that they gave Buddha a human

figure.

The second, located south of New Delhi in Uttar Pradesh, was the Mathura

school (flourished 1st–6th century). In contrast, the Mathuran school is

associated with native Indian traditions that emphasized rounded or voluptuous

bodies adorned with minimal clothing, typically carved out of mottled red

sandstone from local quarries.

Emergence

of Buddhism and Jainism helped in the development of early architectural style.The Buddhist Stupas were built at

places where Buddha’s remains were preserved and at the major sites where

important events in Buddha’s life took place.

·

- STUPAS were built of huge mounds of mud, enclosed in carefully burnt small standard bricks. One was built at his birthplace Lumbini

- the second at GAYA where he attained enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree,

- the third at SARNATH where he gave his first sermon

- and the fourth at KUSHINAGAR where he passed away attaining Mahaparinirvana at the age of eighty.

- Buddha’s burial mounds and places of major events in his life became important landmarks of the significant architectural buildings in the country. These became important sites for Buddha’s order of monks and nuns - the sangha. While Buddhists and Jains began to build STUPAS, VIHARAS AND CHAITYAS, the first temple building activity started during the Gupta rule.

Characteristics of Jain sculpture

Practiced in India since the 6th century BCE, Jainism is a religion that advocates non-violence towards all living things, along with an austere lifestyle. The word "Jainism" comes from from jina (meaning liberator or conqueror), the name given to the 24 main adepts and teachers of this faith. Also known as also known as tirthankaras (river-forders), these 24 individuals are the principal focus of Jain sculpture. The highest form of life in Jainism is the wandering, possessionless, and passionless ascetic, which is why jinas are typically portrayed in statues or reliefs as itinerant beggars or yogis. Invariably they are depicted in only two positions: either sitting in the lotus posture (padmasana) or upright in the Jain body-abandonment posture (kayotsarga).

Practiced in India since the 6th century BCE, Jainism is a religion that advocates non-violence towards all living things, along with an austere lifestyle. The word "Jainism" comes from from jina (meaning liberator or conqueror), the name given to the 24 main adepts and teachers of this faith. Also known as also known as tirthankaras (river-forders), these 24 individuals are the principal focus of Jain sculpture. The highest form of life in Jainism is the wandering, possessionless, and passionless ascetic, which is why jinas are typically portrayed in statues or reliefs as itinerant beggars or yogis. Invariably they are depicted in only two positions: either sitting in the lotus posture (padmasana) or upright in the Jain body-abandonment posture (kayotsarga).

Hindu Sculpture of the Gupta

Empire (flourished 320-550)

The Gupta era is often referred to as the Classical or Golden Age of India, and

was characterized by extensive inventions and enormous progress in technology,

engineering, literature, mathematics, astronomy and philosophy, that laid the

basis for what is generally termed Hindu culture. During this period, Hinduism became the official religion of the Gupta

Empire, which saw the emergence of countless images of popular Hindu deities

such as Vishnu, Shiva, Krishna and the goddess Durga. But the period was

also a time of relative religious tolerance: Buddhism also received royal

attention, while Jainism also prospered. In fact, thanks to the influence of

the Mathura school, the Gupta era is associated with the creation of the iconic

Buddha image, which was then copied throughout the Buddhist world. The Gupta

style of sculpture remained relatively uniform across the empire.. The most

innovative and influential artistic centres included Sarnath and Mathura. The Gupta idiom spread across much of India,

influencing artists for centuries afterward. It also spread via the trade

routes to Thailand and Java, as well as other countries in South and Southeast

Asia.

An important phase of Indian

architecture began with the Mauryan period.

In the Mauryan period

(322-182 BC) especially under Ashoka architecture

saw a great advancement. Mauryan art and architecture depicted the influence of Persians and Greeks.

During the reign of Ashoka many monolithic stone pillars were erected on which

teachings of ‘Dhamma’ were inscribed. The highly polished pillars with animal

figures adorning the top (capitals) are unique and remarkable. The lion capital

of the Sarnath pillar has been accepted as the emblem of the Indian Republic.

Each pillar weighs about 50 tonnes and is about 50 ft high. The stupas of Sanchi and Sarnath are

symbols of the achievement of Mauryan architechture.

The blending of Greek and Indian art led to

the development of GANDHARA ART

which developed later. The other schools of art and architecture were the

indigenous Mathura school and Amaravati school. A large number of statues of

the Buddha were built by the artisans of these schools specially after first

century AD under the influence of the Kushanas.

Under

the GANDHARA SCHOOL of art life-like statues of Buddha and Bodhisattavas were

made in the likeness of Greek gods even, though the ideas, inspirations and

subjects were all Indian. Rich ornaments, costumes drapery were used to impart

physical beauty. The sculptures were in stone, terracotta, cement like material

and clay.

Cave architecture

The development of cave architecture is another

unique feature and marks an important phase in the history of Indian

architecture. More than thousand caves have been excavated between SECOND CENTURY BC AND TENTH CENTURY AD.

Famous among these were

AJANTA

AND ELLORA CAVES OF MAHARASHTRA, and

UDAYGIRI

CAVE of Orissa. These are Buddhist viharas, chaityas as well as mandapas and

pillared temples of Hindu gods and goddesses.

THEKAILASH

TEMPLE AT ELLORA built by the Rashtrakutas and

the

RATHA TEMPLES OF MAHABALIPURAM built by the Pallavas are other examples of

rock-cut temples. In southern India the Pallavas,

Cholas, Pandyas, Hoyshalas, Later the Rulers Of The Vijaynagar kingdom were

great builders of temples.

The

PALLAVA rulers built the shore temple at Mahabalipuram.

Pallavas also built other structural

temples like KAILASHNATH TEMPLE AND VAIKUNTHA PERUMAL TEMPLES at Kanchipuram.

Pallava

and Pandya Sculpture from South India (600-900)

Nearly all the sculpture created

in southern India during the 7th, 8th and 9th centuries, is associated with the

Pallavas or the Pandyas - the two most important Hindu dynasties of the time.

Pallava rule was centered on the eastern coastline and included the city of

Mamallapuram, in the Kancheepuram district of Tamil Nadu, which was famous for being

the site of the carved-stone cliff created by Pallava kings in the 7th century.

The Pallava era is significant for marking the transition from rock-cut architecture to stone temples.

Its best-known achievements include the Kailasanatha

temple in Kanchipuram (685-705) noted for its huge pillars ornamented with

multi-directional carvings of lions, and the Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram (7th century), overlooking the Bay of

Bengal, which was decorated with copious stone statues and reliefs of Vishnu,

Shiva, Krishna and other Hindu deities.

Nearly all the sculpture created

in southern India during the 7th, 8th and 9th centuries, is associated with the

Pallavas or the Pandyas - the two most important Hindu dynasties of the time.

Pallava rule was centered on the eastern coastline and included the city of

Mamallapuram, in the Kancheepuram district of Tamil Nadu, which was famous for being

the site of the carved-stone cliff created by Pallava kings in the 7th century.

The Pallava era is significant for marking the transition from rock-cut architecture to stone temples.

Its best-known achievements include the Kailasanatha

temple in Kanchipuram (685-705) noted for its huge pillars ornamented with

multi-directional carvings of lions, and the Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram (7th century), overlooking the Bay of

Bengal, which was decorated with copious stone statues and reliefs of Vishnu,

Shiva, Krishna and other Hindu deities.

The Pandya dynasty, based further

south in the vicinity of Madurai, Tamil Nadu, ruled parts of South India from

600 BCE to first half of the 14th century CE. Like the Pallavas, the Pandyas

were famous for their rock-cut architecture and sculpture. The latter is

exemplified by the granite statue of a Seated four-armed Vishnu (770-820), now

in the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York.

Chola Bronze Sculpture of South

India, Sri Lanka (9th-13th

century)

From the late 9th century to the

late 13th century the Chola dynasty ruled much of south India, Sri Lanka and

the Maldive Islands from their base near Thanjavur on the southeastern coast.

Chola kings were active patrons of the arts, and during their reign they built

a number of large stone temple complexes decorated throughout with stone

carvings of Hindu deities. However, Chola art is best-known for its temple bronze

sculpture of Hindu gods and goddesses, many of which were designed to be

carried in local processions during temple festivals. Cast using the lost-wax

method, Chola bronzes were admired for their sensuous figures as well as the

detail of their clothing and jewellery. It is worth remembering that when these

images were worshipped in the temple or during processional events, they were

lavishly adorned with silk cloth, garlands, and jewels. The Chola style of

sculpture was greatly admired for its elegance and grace, but especially for

its vitality - an attribute conveyed through facial expression, posture and

movement. Even though bronze sculpture was well established in south India

before the Cholas, a much greater number of bronze statues were created during

the Chola period. Chola Hindu sculpture features countless figures of Shiva,

often accompanied by his consort Parvati; Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi; the

Nayanmars, other Saiva saints and many other Hindu divinities. The CHOLAS built many temples most famous

being the BRIHADESHWARA TEMPLE AT TANJORE. The Cholas developed a typical style

of temple architecture of south india called THE DRAVIDA STYLE, complete with

Vimana Or Shikhara, high walls and the gateway topped by gopuram.

MUGHALS

From 1526 until 1857, much of

northern India was ruled by the Mughals, Islamic rulers from Central Asia.

During this era, the principal artistic activity was painting, while metalwork, and ivory

carving as well as marble

sculpturealso flourished..

The Mughal Emperor Akbar was an

enthusiastic patron of stone carving. He commissioned statues of Jai

Mal and Fatha (Rajput heroes of Chittor) shown sitting on elephants, to

guard the gate of the Agra Fort.

Emperor Jahangir erected two life-size

marble statues of Rana Amar Singh and his

son Karan Singh in the palace garden at Agra.

In general, Mughal rulers were

great admirers of relief

sculpture (including abstract work as well as naturalist depictions of

flowers, butterflies, insects and clouds) which was regarded as an essential

element of Mughal architecture, and embellished their buildings with a wide

variety of this type of decorative

art: an example being the 50 varieties of marble carving on the walls

of Akbar's tomb at Sikandra

The

first building of this rule was HUMAYUN’S

TOMB at Delhi. In this magnificent building red stone was used. It has a

main gateway and the tomb is placed in the midst of a garden. Akbar built forts

at Agra and Fatehpur Sikri.

The

tomb of Salim Chishti, Palace of Jodha Bai, Ibadat Khana, Birbal’s House and

other buildings at Fatehpur Sikri reflect a synthesis of Persian and Indian

elements Fatehpur Sikri is a romance of

stones.. During the reign of Jehangir, Akbar’s Mausoleum was constructed at

Sikandra near Agra. He built the beautiful tomb of Itimad-ud-daula which was

built entirely of marble.

Shahjahan

was the greatest builder amongst the Mughals. The Red Fort and Jama Masjid of

Delhi and above all the Taj Mahal are some of the buildings built by Shahjahan.

The Taj Mahal, the tomb of Shahjahan’s wife, is built in marble and reflects

all the architectural features that were developed during the Mughal period..

The Mughal style of architecture had a profound influence on the buildings of

the later period. The buildings showed a strong influence of the ancient Indian

style and had courtyards and pillars. For the first time in the architecture of

this style living beings- elephants, lions, peacocks and other birds were

sculptured in the brackets

COLONIAL

ARCHITECTURE AND THE MODERN PERIOD